The Null Device

Posts matching tags 'jeremy corbyn'

2017/6/9

Well, that was interesting.

It was an unnecessary election, called by a brittle authoritarian Prime Minister, hoping to take advantage of an unpopular and discombobulated opposition to get a sweeping mandate to remake the country. Aware of the near certainty of victory, they packed their manifesto with far-reaching ambit claims: force the NHS to sell off its land; replace Britain's segment of the internet with an Iranian-style censored, filtered national intranet and ban strong encryption; replace local election voting systems with first-past-the-post, killing off minor parties, abolish the Serious Fraud Office (which had an unfortunate habit of picking on Tory MPs); they even included ending a ban on the ivory trade, because, why not. And it looked like it would win; all the polls showed commanding leads. Britain would vote Conservative, because it believed it deserved to be punished. Or perhaps, however unpalatable the Tories' programme was, the alternative was unthinkable, so bitter medicine it would have to be.

Things tightened during the election. (It didn't help that Theresa May didn't cope all that well when things weren't under her control, and tended to freeze up like a broken Dalek when confronted with questions from members of the public; empty warehouses and squads of pre-vetted party volunteers were soon found to mitigate this.) Things, however, could be expected to tighten. It's all part of the pantomime of the great carnival that is a general election: the old order is temporarily inverted and those who govern are briefly at the mercy of their subjects. Still, the vast majority of polls pointed to an increased Tory majority, if not quite the epic landslide promised, but still a healthy mandate.

It didn't work out that way. As soon as the polls closed, the exit poll (which has a much higher sample size and resolution) indicated a hung parliament. As the night went on, this bore out in results: Tory seats falling to a Labour party buoyed by an unusually high turnout, especially of young people traditionally written off as apathetic. (Somehow enough millennials took a break from Snapchatting selfies or eating avocado toast in pastel-coloured onesies or whatever it is the snake people reportedly spend all their time doing and got out to vote, swinging entire seats. One can probably add neoliberalism to the list of things millennials are ruining.) By the morning, a hung parliament was confirmed.

May didn't waste any time, and secured a minority-government deal with the Democratic Unionist Party, a far-right religious-fundamentalist party from Northern Ireland with shadowy links to Protestant paramilitary groups; together, they have a working majority of one or two seats. Things get interesting when one considers that the DUP are opposed to the restoration of a hard border in Ireland (making leaving the customs union much more complicated), but also opposed to Northern Ireland having any special status within the EU (as that'd be caving in to the papists south of the border). They get even more interesting factoring in the fact that a significant number of the Tories' MPs are in Scotland (where the SNP had a very bad night), and thus prohibited by the English Votes for English Laws convention from voting on purely England-and-Wales matters (such as anything to do with the NHS or education). If this holds (and, in the ad hoc world of Westminster, especially under the reality distortion field of a right-wing press, nothing is certain), it means that the government will not have a majority to pass much of its programme; and even that which isn't covered could fall prey to dissent within the party. A further question is that of Theresa May's career. She may have reasserted her authority over her party for the time being, but she did gamble on an unnecessary election, and the Conservatives' losses are at least partly due to her performance. History's judgment of May will not be favourable; as Charlie Brooker put it, “the history books will say Theresa May poured her legacy into an upturned crash helmet and shat in it.”) Meanwhile, Boris Johnson (the classically eloquent yet buffoonish Bullingdonian partly responsible for the whole Brexit omnishambles thast led us here) is said to be preparing for a challenge. Which could mean that, soon, both sides of the pond will be ruled by the hosts of a species of hirsute parasitic brain slug.

If there is a winner of the night, it is the Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. Previously written off as unelectable, Corbyn has galvanised the party base and the voting public, and achieved the highest vote count for Labour since Tony Blair swept to power 20 years ago. And it's Blair's legacy—a focus-grouped managerialism, bedded on the certainty of Margaret Thatcher's neoliberal axiom, “there is no alternative”—that Corbyn has put to rest. It will be a long time until we see a bland, well-scrubbed Labour politician announcing that the party has the value of “having strong values” or some similarly content-free pabulum. And given the Tory minority government's tiny working minority, and the certainty of byelections, Corbyn may yet be Prime Minister sooner rather than later.

In summary: strap in. This ride's just beginning.

2017/4/18

Seemingly inspired by Turkish strongman Erdoğan's resounding 52-48% victory over the weekend, UK Prime Minister Theresa May has called a snap general election for 8 June, calling a vote to overturn the 2011 Fixed Parliaments Act in the process. With Labour in disarray, the election will almost certainly result in a Conservative landslide and an Erdoğan-sized mandate to reshape the United Kingdom as it leaves the European Union to become a sort of Singapore of the Atlantic; undercutting the decadent vino-drinking continentals with lower taxes, wages and regulations, and a workforce that knows its place (because any other places it could have gone for a better deal have forever been closed off) and making common cause with the world's tyrants, no longer shackled by politically-correct notions of “human rights”.

The Labour Party would nominally be the opposition to the Tories, as they were throughout much of the 20th century, though are not providing much of an opposition. Under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, a pre-Blairite socialist once written off as a relic of a bygone era, they have swung firmly in favour of Britain leaving the European Union, whipping their MPs to support Article 50. This is either in an attempt to win back the xenophobic vote or out of some delusional belief in the myth of “Lexit” (left-wing Brexit): the delusion that, having cut its ties with the neoliberal free-marketeers of the European Union, Britain will be free to become a sort of rainy Cuba, a pre-Thatcherite socialist arcadia where the coal mines never closed, the state-run supermarkets only stock one variety of tea, and we're all somewhat poorer and shabbier but equal and happy, all watched over by a cadre of shop stewards in ill-fitting brown suits. On the issue of leaving the EU, there is no difference between the two parties; only on the mythology and teleology of what doing so will signify.

It wasn't always like this, but it was for longer than many would think. When Corbyn ran for the Labour leadership, he was an outsider candidate, put forward half-jokingly next to a field of focus-grouped Blair-manqués struggling to find a selling point for Labour. (One of them actually said that one of Labour's values is “having strong values”; the mutability of those values, presumably, making it easier to respond to polling and market research.) A candidate who actually believed in something—not to mention something as radical as socialism (but not to worry, democratic socialism)—was quite exciting. Corbyn prevailed by a broad margin and saw off several leadership coups (attributed to either traitorous neoliberal Blairites or ordinary Labour MPs questioning their new leader's ability to actually lead, depending on whom one listens to); he is currently presiding over the “regeneration” (and, inevitably, downsizing) of Labour into a more traditionally leftist direction, albeit without the benefit of shipyards, steelworks and mines full of dues-paying industrial workers to provide a natural constituency for a party of labour. (Labour, of course, started as an offshoot of the union movement, a parliamentary party for those whose stake in the system was their labour, rather than property or pedigree. This raison d'être began to diminish with the shift away from heavy industry, which started in the 70s but accelerated under Thatcher; by the 90s, it was a ghost of its former self. It was mostly Britpop-fuelled euphoria and/or Tony Blair's Bonoesque charisma that kept Labour going, with New Labour's Tory-lite policies attracting a critical mass of centrist careerists who wouldn't have touched socialism with a bargepole, and whom Corbyn is now doing his best to purge. That and Thatcher having tested the hated Poll Tax in Scotland, delivering virtually that entire country to Labour, in time for it to shore up Blair's successive administrations; though the Tories shrewdly wiped this out by convincing Labour to lead the No campaign against Scottish independence, and so deliver their entire base there to the Scottish National Party, effectively holing Labour below the waterline. So, in summary, the revival of Labour in the 90s was about as substantial as the revival of Swinging Sixties cool that the music journalists of the time were going on about the latest Blur/Oasis/Elastica single being the epitome of.)

The problem with this new direction for Labour is that it jettisons many of the tenets of liberalism and openness. Corbyn made only the most half-hearted and token attempts at campaigining to remain in the EU, and once the result was in, enthusiastically jumped to the victorious side. Protectionism trumps openness; nationalism trumps solidarity.  The traditional anglosocialist utopia of Labour looks a lot like the traditional Little England of UKIP, with its distrust of all things foreign; the only difference is, in one case, there is a strict hierarchy, with everyone knowing his or her place, whereas in the other, everybody's equal (though some are more equal than others; every socialist utopia needs its cadres and vanguard party, after all). As neoliberalism dies, it's the “liberalism” part that is jettisoned; the hierarchies of oppressive power continue, as they always have. (Similarly, across the centre-right parties and think tanks of the world, the dry, bloodless academic writings of Hayek and Friedman are quietly being bumped from reading lists, replaced with Julius Evola and translations of Aleksandr Dugin; Ayn Rand, however, retains her popularity, her message of the inherent rightness of power and privilege, predating the Mont Pélerin Society, will outlive the myth of the tide that lifts all boats.) That Labour is facing electoral slaughter is not much comfort, given that the result will be the coronation of an authoritarian unelected leader into a position of unassailable power to remake the United Kingdom in her image; our own Lee Kwan Yew, or perhaps a British Erdoğan.

The traditional anglosocialist utopia of Labour looks a lot like the traditional Little England of UKIP, with its distrust of all things foreign; the only difference is, in one case, there is a strict hierarchy, with everyone knowing his or her place, whereas in the other, everybody's equal (though some are more equal than others; every socialist utopia needs its cadres and vanguard party, after all). As neoliberalism dies, it's the “liberalism” part that is jettisoned; the hierarchies of oppressive power continue, as they always have. (Similarly, across the centre-right parties and think tanks of the world, the dry, bloodless academic writings of Hayek and Friedman are quietly being bumped from reading lists, replaced with Julius Evola and translations of Aleksandr Dugin; Ayn Rand, however, retains her popularity, her message of the inherent rightness of power and privilege, predating the Mont Pélerin Society, will outlive the myth of the tide that lifts all boats.) That Labour is facing electoral slaughter is not much comfort, given that the result will be the coronation of an authoritarian unelected leader into a position of unassailable power to remake the United Kingdom in her image; our own Lee Kwan Yew, or perhaps a British Erdoğan.

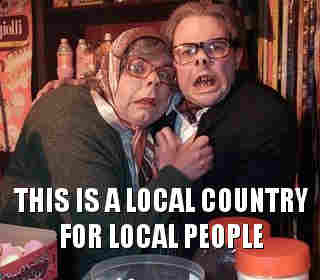

I currently live in the electorate of Islington North. Jeremy Corbyn is my constituency MP, and I voted for him in the last general election, as he was a fine constituency MP. However, he has not shown himself to be a plausible party leader, and after his betrayal on Brexit, I will not be able to vote for him in the upcoming election. I am thinking of voting for the Lib Dems; they are the largest party standing against Brexit and its attendant xenophobic isolationism, and the most likely to unseat Corbyn in liberal, cosmopolitan Islington North. Ordinarily, I would consider the Green Party, or the Pirate Party if they ran here, but in this election, and under the first-past-the-post system, it is important to vote for the lesser evil rather than treating electoral choice as a litmus test of purity of convictions. (See also: Jill Stein, the US Green Party candidate whose electoral messaging seemed almost precisely calculated to undermine Clinton and get Trump into power.) And right now, with the two largest parties offering two different variants on the same Scarfolk-meets-Royston-Vasey dystopia, the role of opposition and/or lesser evil has fallen on the Liberal Democrats.

2016/5/7

The results are in from Thursday's outbreaks of voting across the United Kingdom, and this is how the picture looks:

Labour's results are looking somewhat mixed; in the Scottish parliament, they lost many seats, placing them behind the Conservative Party for the first time since Thatcher's catastrophic Poll Tax (which, actually, was about a generation ago). A lot of this is undoubtedly due to them having been used as a cat's paw by the government-led anti-independence campaign, and thus becoming the Westminster absentee landlords' good cop; they were caned harder than the Tories because it's hard for voters to punish a party who have next to no seats. In England, they lost councils, which is either due to the public being wary of the possibility of Jeremy Corbyn turning Britain into Chavez-era Venezuela, the Labour Party being riddled with cranks who, ominously, really don't like Jews, or to Labour's local representation being at a high water mark since the last elections (when the Lib Dems got a kicking for selling out to the Tories), depending on whom you ask. Having said that, the Tories lost slightly more than Labour did, though given that they're in the middle of a term, presiding over a harsh regime of austerity and soaring inequality, one could argue that anything short of the decimation of Tory councils is, all things considered, a good result for them.

What this bodes for Labour, and its new, stridently left-wing direction under Corbyn, is very much open to interpretation. On one hand, some are hailing not being wiped out south of the border (despite the antisemitism crisis, Lynton Crosby's barrage of dead cats, and everyone but the Guardian urging the public to vote Tory) as a resounding vindication for Corbyn; on the other hand, others are pointing out that the result is comparable to Labour's local-government results in the middle of its Thatcher-era period in the wilderness. Though it appears that the knives are not yet out for Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn. For one, the Labour centre-right does not have a new Tony Blair or similarly charismatic figure to present as an alternative; and indeed, Corbyn the old weirdy-beardy socialist won partly because the slate of “serious”, “respectable” candidates he ran against was an eminently forgettable one. The choice for a potential Labour putsch, at this stage, would be Anyone But Corbyn, and Labour's fortunes have not sunk so low as to necessitate that.

The outcome is also a mixed one for the Conservatives. Their campaign for London was led by Zac Goldsmith; youngish, fabulously wealthy and with a history of environmental campaigning behind him. Which could have boded for a hearts-and-minds campaign: promote Goldsmith as a liberal, a broad-minded unifier who cares about progressive causes, winning over the metropolitan cosmopolitan types who don't care much for right-wing red meat, and he could have spent the next four years alternately having photo opportunities with minority groups, making motherhood statements about diversity and the environment, and quietly promoting the transformation of everywhere inside the M25 into an enclave for global wealth. However, the Tories appear to have been seduced by the siren song of roving ratfucking consultant Lynton Crosby. Crosby's dirty tricks did win them the last general election, so presumably early in Goldsmith's campaign the order came down from on high to play the man, not the ball: keep pointing at Labour's candidate, Sadiq Khan, and mumbling darkly about Islamic terrorism, in the hope that the mud would stick. It didn't; Khan won handsomely, and now the political career of Goldsmith, the former golden boy of progressive conservatism, lies in ruins. Perhaps he wasn't actually a bigot, but merely too weak-willed to have pushed back against the bigots, though the result is the same; in any case, it's now his role to serve as an example to other political hopefuls who might be tempted to huff the intoxicating jenkem of bigotry.

In other news, the Green Party did well in London; their mayoral candidate, Siân Berry, came third (overtaking the Liberal Democrats), and they kept their two seats on the council. Labour fell short of a majority on this council, which stands the Greens in good stead to hold their feet to the fire on, say, diesel emissions or cycling infrastructure. As for the hapless Lib Dems, they seem to be gradually clawing their way back from their abyss. Ominously, the hard-right UKIP party seems to have picked up some two dozen seats.

2015/9/13

In news that wasn't entirely unexpected, Jeremy Corbyn has been elected to lead the Labour Party in Britain. Corbyn, a left-wing veteran backbencher and frequent parliamentary rebel, had originally been entered into the contest shortly after Labour's crushing election defeat for the purpose of “broadening the debate”, and possibly generating some ideas that could help towards the next campaign of whoever won. The tones of the sensible post-ideological managerialists in the party began to darken when Corbyn started leading the polls; why would an ancient weirdy-beardy lefty given to wearing shabby home-made jumpers outpoll all those polished talking heads, with their extensively tested motherhood statements about “social justice” and “aspiration”, about doing something about “inequality” whilst giving no quarter to unworthy scroungers, balanced in the optimum proportion given the most recent polling? Whatever hope remained of “shy Blairite” tendencies prevailing in the actual ballot were annihilated when the results came in: Corbyn got 59.5% of the vote in the first round, almost three times as many as his nearest challenger, Andy Burnham. Meanwhile Liz Kendall, a Blairite candidate representing the notion that, following its electoral defeat, Labour must move to the right, came in last with a dismal 4.5%. (Tony Blair himself, meanwhile, phoned in from whichever despot's yacht he is currently staying on, urging the Labour faithful to vote for anyone but Corbyn; the fact that, from Blair's point of view, all the other candidates were interchangeable, is telling. In any case, it's not unlikely that a significant number of people voted for Corbyn partly to give Blair a kicking.)

Of course, it is easy enough to get elected to be leader of the opposition; as leader of the Opposition, Corbyn's mandate is to lead the party into the next election, and into government; whether that is possible is an open question. One common narrative says that Corbynmania is a purely emotive movement, grasping for the comfort of a fantasy, or the righteousness of the lost cause, much in the way that the hopeless embrace apocalyptic religion or conspiracy theories, and that, in the dozens of Tory marginal seats Labour will have to win back, it's unlikely to find traction. The implication of this narrative is that the opposite, a skilful rightward-triangulating neo-Blairism, cheekily ambushing the Tories on their own ideological turf, whilst offering the slightest essence of a brighter alternative—socialism diluted to homeopathic proportions, so not one particle remains—to somehow push the feeling that a Labour government implementing neoliberal privatisation/austerity policies will be ineffably better. This neo-Blairite model would place the running of the country in the hands of technocratic management, operating under a neoliberal free-market framework (as There Is, after all, No Alternative), communications with the fickle masses in the hands of spin doctors and, essentially, disinformation specialists, and whatever policy is not dictated by the markets and the needs of corporate stakeholders would be subject to focus groups and opinion polls. Standing for something is for losers, after all.

There are several problems with this argument; not least of them the fact that the Labour Party fielded three candidates who were driven by such calculation, who did dismally. Indeed, the one who did the worst was the one who most honestly articulated a Blairite centre-right position of the sort that, we are told, is catnip to the ordinary voter (the ordinary voter; that sharp-elbowed aspirational creature that reads the Evening Standard and is concerned primarily about their property values). The other two kept it artfully vague, avoiding committing to anything that might be held against them, hitting the talking points like pros, and even tacking to the left when it became evident that Corbyn had shifted the party's internal Overton window; it didn't do them much good. Had one of them won, it is hard to imagine their warmed-over, cobbled-together message stirring the electorate; especially whereas none of them had Blair's Mephistophelian charisma. (On the other hand, it can be argued that Tony Blair's uncanny election-winning power has been somewhat overstated; in 1997, the Conservative government was in such disarray, with a series of scandals and misfortunes topping a general sense of malaise and decay, that chances are anybody could have led Labour to victory.)

Anyway, it is now Corbyn's task (along with the newly elected deputy leader, Tom Watson, who's more of a pragmatist, whilst simultaneously passionate about issues of civil liberties) to lead the party into the next election and win. And one thing we can expect is that they will come under withering fire; from the Tories, the right-wing press, and even the more Blairite elements of their own party, should they sense the opportunity for a spill. From now on, the press will be full of hit pieces of varying degrees of hyperbole (look for mentions of “the Chavez of Canonbury”, for example). And perhaps the public will, after enough repetitions, start to believe them; polls will show Labour's support deteriorating; perhaps they will go into the next election and be thoroughly annihilated, swapping places with the Liberal Democrats; or not even get that far, as MPs, facing the loss of their seats, stage a spill and hurriedly put on their best Blairite act. But perhaps this time it won't work; if the Tories miscalculate, if too many of the public know people who have been thrown on the scrapheap by austerity, if the idea that those hit by welfare sanctions or the bedroom tax are the “unworthy poor” who have made their own misfortune through fecklessness suddenly loses its power, if millions of people realise that they're not temporarily embarrassed buy-to-let multi-millionaires but rather the deeply indebted precariat, and that the windfall they anticipate is not about to trickle down to them any time soon, the scare stories will be dismissed, and, being inured to them, the public will dismiss any concerns about Corbyn's views as similarly concocted.

Personally, I agree with some of Corbyn's views, but not all. He is my local MP, and I have, on occasion, written to him about various issues, and generally found my concerns well received. I'm not so keen on some of his other cited positions, such as, for example, withdrawing from NATO or the EU, or spending public health funds on ineffectual mystical quackery such as homeopathy. More significantly, Corbyn's idea of reopening coal mines seems backward in this day, when China and India are slashing their coal imports, coal-fired power plants are being deprecated and not replaced, and even coal-mad Coalition-ruled Australia is having a hard time funding its new coal mines. Corbyn's hope of reopening coal mines seems similarly ideological, only rather than impressing the bogan voters by punching the inner-city latte-sippers, it looks to be about avenging Arthur Scargill and the martyrs of Orgreave and sticking one up at Thatcher. Indeed, Corbyn doesn't seem to have said much about the environment or the threat of climate change, or the need to radically change our infrastructure to reduce its environmental impact.

However, Corbyn is not the autocratic leader of the Labour Party, and it seems that these positions are less likely to prevail than more popular ones (such as building massively more public housing, renationalising the railways, easing off on austerity and such).

In any case, we live in interesting times; as the last election (in which the SNP took almost a clean sweep of Scotland) showed, we can no longer rely on safe assumptions of how things will unfold.